A female cleric. Men and women praying together in the same room. Berlin’s liberal mosques are working toward an Islamic reformation, all while avoiding death threats.

By Sebastian Leber | Published on September 21, 2018 5:45 pm

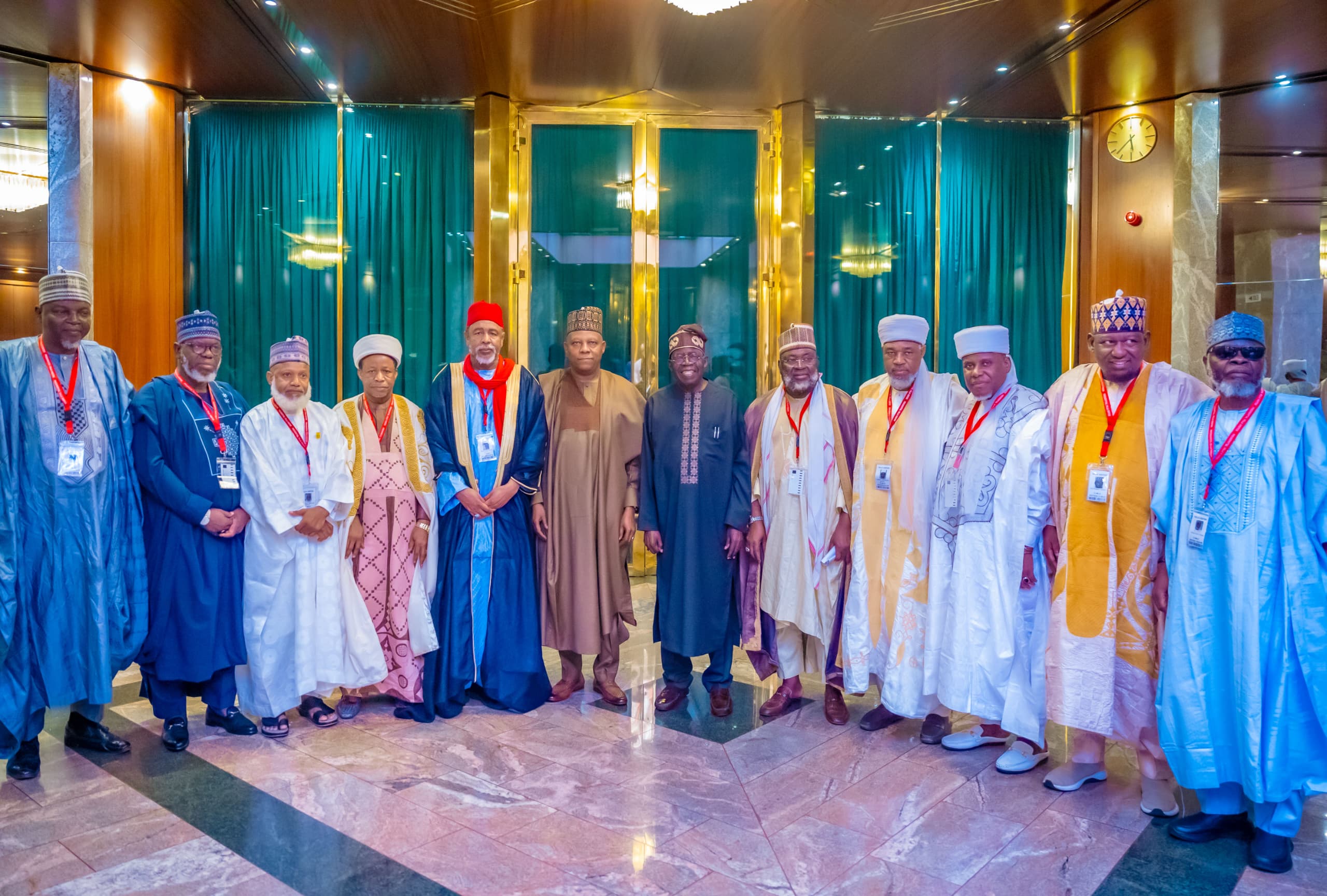

German security services were recently in touch with one of Berlin’s best-known Muslim clerics. He should take their warnings seriously, they again told Abdul Adhim Kamouss. Death threats were being made against him by members of the Islamic State extremist group and they were real, the officers said.

Mr. Kamouss knows why he is being threatened but he will continue with his plans. The 41-year-old Berlin local wants to start his own mosque, where he will preach mainly in German; he also wants to establish an advisory service for Muslims, a center to combat radicalization and a Muslim scout group.

To do all this, Mr. Kamouss started a foundation called Islam in Germany. He sees himself as somebody who will bring his religion into the 21st century, encouraging his congregation to play a larger role in mainstream German culture and fighting what he calls “the rat catchers” – radicals who preach a hateful version of his religion to entice younger Muslims to do their bidding.

A popstar for religious extremists

Mr. Kamouss wasn’t always this way. He used to preach in a radical mosque in Berlin’s Neukölln district that was under observation by state security. Back then, he thought good, Muslim women should never leave the house and that bad Muslims would all go to hell. In fact, Mr. Kamouss was famous for strict adherence to the toughest of Koranic edicts.

Local media described him as “a brainwasher” and “a pop star on the Salafist scene” (Salafists being among the most extreme believers from the Sunni branch of Islam, from which the Islamic State also arose). One of Germany’s most infamous terrorists, former rapper Denis Cuspert, who was later seen in Islamic State videos, used to come to Mr. Kamouss’ tough-talking sermons.

Then his message changed. There was no need to wear the full-face-and-body veil known as the burqa or to avoid having men and women shaking hands. He encouraged Muslims to vote and to take part in the culture in which they live, as opposed to separating themselves from what he had previously seen as the “unholy” sphere.

In August, Mr. Kamouss, who has been described a traitor to his own religion, a German suck-up, released a book about his personal transformation: “Wem gehört der Islam?,” or “To whom does Islam belong?” The message is clear: Islam needs a reformation. His book is also critical of local Muslim organizations: Why is it that they can’t offer services in German? Why must they bring clerics from the Turkish, Egyptian and Moroccan countryside, who know nothing about life in contemporary Germany?

Conservative views only, please

There are some 98 prayer rooms and mosques throughout the city, but it is predominantly the larger mosques and associations who speak for the metropolis’ 250,000 to 300,000 Muslims. They tend to be on the conservative end of the spectrum, both in religious and political terms.

A lack of alternatives means the German government and media often turn to these organizations for the Muslim point of view at interfaith events. This was one complaint about the new Institute for Islamic Theology, where potential clerics and preachers can study, that is scheduled to open at Berlin’s Humboldt University next autumn. Three large Islamic associations were asked to advise on teachers and course content. Far-smaller, liberal organizations were not included.

One of the smaller organizations that complained, the Ibn Rushd-Goethe mosque, is headquartered three kilometers from Mr. Kamouss’ currently-makeshift mosque.

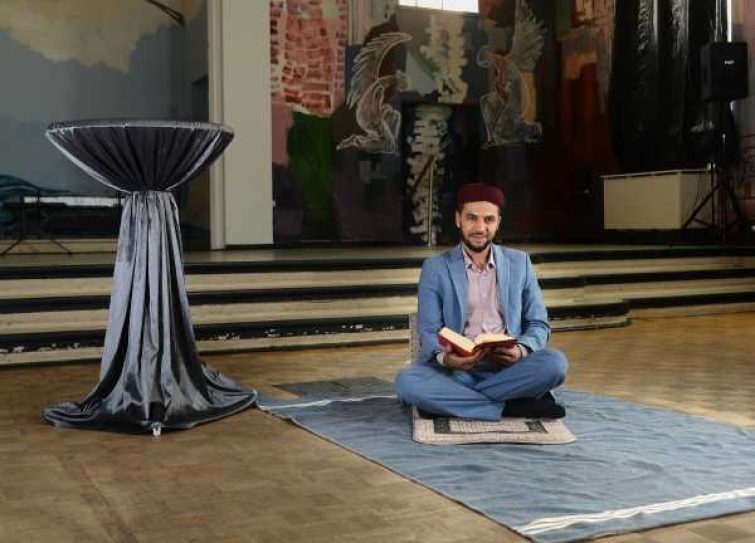

On a Friday afternoon, just before services are to begin, about two dozen people crowd the small prayer room. Some participants are kneeling on prayer mats, others are seated on chairs around the walls, watching. The observers, not here to pray, include Christians, non-believers and local Muslims.

They’re intrigued because the German mosque allows men and women to pray together. A female celebrant is leading the prayers today. That alone is a complete anathema to most Muslims, conservative or otherwise, and the mosque and its founder, human rights lawyer Seyran Ates, have been loudly criticized and threatened. In Ms. Ates’ case, that includes being physically attacked and shot at.

Although Ms. Ates says she won’t be discouraged, it seems a lot of Muslims are: There are usually only around 25 praying at the mosque. “That doesn’t mean there is no interest,” Ms. Ates explains. “It just means that people are intimidated.”

A guest asks why prayers are held Friday afternoon when many people are still at work. It’s a tradition from the Middle East, Mohammed replies. Given that the mosque is bucking a fair few stereotypes, they decided to keep that tradition. “A lot of Muslims are already accusing us of wanting to change too much,” Mohammed adds. “They say we want to start a whole new religion.”

Sebastian Leber is a reporter with Handelsblatt’s sister publication, the daily Tagesspiegel. This story was adapted from the German for Handelsblatt Global. To contact the author: [email protected]