Islamophobia in France and Britain has intensified in recent years, particularly in the wake of terrorist incidents, such as the 2015 Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris and the London Bridge attack. This led British prime minister, Theresa May, and French president, Emmanuel Macron, to meet in January 2018 to agree a shared approach to counter-terrorism.

In many respects, France and Britain face similar challenges. They are both in Western Europe and have significant Muslim populations. It’s estimated there are 5.7m Muslims in France and just over 2.7m in the UK. But our research shows that Islamophobia operates differently in each country.

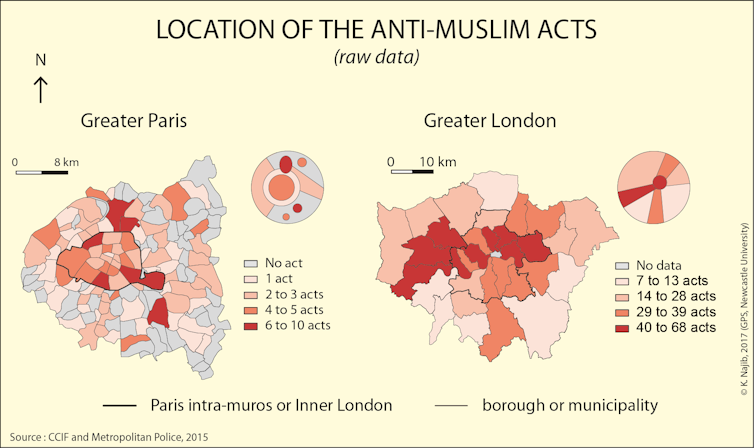

In an effort to shed light on the complexities of Islamophobia, our research into anti-Muslim acts focuses on where Islamophobia happens in France and the UK – mainly in Paris and London. Data from 2015 from the associations Collectif contre l’islamophobie en France (CCIF) in France and Tell MAMA in the UK reveal the specific contexts of Islamophobia.

In both countries, most anti-Muslim acts take place in the two capital cities, but the distribution of Islamophobic acts varies. In Paris, anti-Muslim acts take place more in the Parisian centre and they decrease progressively the further out from the centre you go. This creates a contrast between the centre and the suburbs.

This is different to London, where there are similar numbers of Islamophobic incidents in both inner and outer London. Many anti-Muslim acts take place on buses and trains, or in transport hubs. The phenomenon is therefore spatially more diffuse, because anti-Muslim acts occur mainly in everyday spaces.

Latifa, who took part in our research in London, explained to us that:

A man walking onto the bus decided to lean over me, and directed a few derogatory Islamophobic comments calling me ‘ISIS terrorist’ – he was actually touching me.

In France, the majority of Islamophobic acts take place in public institutions such as a town hall, a school or a hospital. In Paris, most anti-Muslim acts are based around personal discrimination. One of the people we interviewed in France, Kenza explained:

One of my friends arrived in the school, while the director snatched her veil in front of everyone. I always have this image in my head, seeing her climbing up the stairs ashamed.

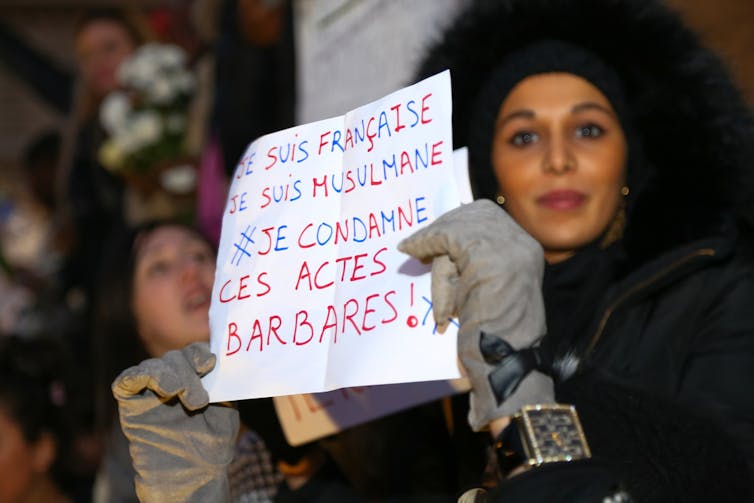

The reason why most discrimination takes place in public institutions is largely due to the impact of a 2004 French law which bans the headscarf in state-funded schools, in the name of laïcité or secularism. Some civil servants – whether they know the law or not – believe that they have the right to extend its scope to all the users of diverse public institutions and not only schools. While the wearing of the niqab, or full face veil, has been banned in public in France since 2010, headscarves are not. As a result, Islamophobia in France is more institutionalised.

Different victims and perpetrators

In both France and the UK, the main victims are veiled Muslim women and in France, many of them are students. Victims in the UK tend to have a South Asian background, while in France they tend to be from North Africa. This connects with the immigration history and colonial past of each country.

White men are the main perpetrators of anti-Muslim acts in the UK. In France, it is equally likely to be a man or a woman. Some French women – notably French feminists – resist the wearing of the veil, and consider that a hijabi woman cannot be a feminist. In the UK, Islamophobia is often related to white men’s domination over ethnic and religious minority women.

The role of the state

Our findings consider the role of the state in fostering where and how Islamophobia happens. The French republican model sees all citizens as French and does not differentiate between people on the basis or race or religion. This could partly explain why there are fewer Islamophobic acts reported in France as it is challenging to make a claim based on religious intolerance or racial discrimination when such divisions are not easily recognised by the French state.

The UK tends to promote an approach that is built around multiculturalism and the promotion of diverse ethnic and religious communities. Unfortunately, some resist this multicultural approach and are racist against those who they feel do not “belong” in the UK. These factors are also likely to shape how Muslim communities engage in politics and participate in society.

Both the French and British approaches demonstrate the role that the state plays in shaping where anti-Muslim acts take place and who is involved. The state has been described as one of the five pillars of Islamophobia – so the governments in both countries should be more critical and aware of the role their policies play in shaping everyday experiences of Islamophobia.