MUZAFFARNAGAR, India (RNS) — Vakeel Ahmad was stirring spiced milk tea at his shop, Chai Lovers Point, lined up alongside a national highway in Uttar Pradesh, when the police pressed him to rename the stall.

Ahmad then called it “Vakeel Sahab Tea Stall.” Also spelled saheb, the term translates to a version of “sir” in Hindi but is a loan word from Arabic. It was not clear enough, he was told. He had to rename it “Vakeel Ahmad Tea Stall,” Ahmad told Religion News Service, using his last name “to make clear of my Muslim identity.”

Like Ahmad’s, thousands of eateries along a route that an estimated 30 million Hindu pilgrims are traveling this week have come under pressure to display the names of their owners and staff to help customers avoid certain food and beverage outlets. Devotees of Lord Shiva walk over 60 miles to collect water from the Ganges River and bring it home as an offering.

You may be interested

Soon, similar dictates emerged from other states ruled by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party. The two-week-long pilgrimage runs from July 22 to Aug. 6. During that time most of the devotees avoid eating meat, onions or garlic. Ahmad’s stall sells only chai and packaged snacks such as chips and cookies.

The order from the local administration sparked widespread outrage for its “bigoted nature,” said Nadeem Khan, the national secretary of the Association for the Protection of Civil Rights, a human rights group. Khan and other critics of the government called the order another step toward “apartheid” and the continued persecution of caste- and religion-based minorities in India.

Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, is governed by Yogi Adityanath, a Hindu nationalist leader of Modi’s BJP known for his inflammatory remarks against Muslims. Under his leadership, violence against Muslims in his state has surged.

“The Kanwar Yatra used to be the time for our business,” said Ahmad, who took over the small business after his father’s death six years ago. “Now, the administration has completely given up on us, saying, ‘If the pilgrims attack you, it is on you — and you will have to deal with it.’”

On July 22, India’s top court paused the government’s divisive directive that would have demanded owners to display their names. The stay order came in response to petitions filed by human rights advocates.

That has brought little relief in Ahmad’s life, though. “I have closed the shop now because things are getting out of control,” he told Religion News Service, referring to the string of incidents of vandalism and attacks by the devotees as the pilgrimage proceeds.

“We thought we could withstand the pressure, but it is not possible anymore,” he said. “My family is incurring losses. Is this a festival?”

The two new signboards cost him $40, nearly half his monthly income.

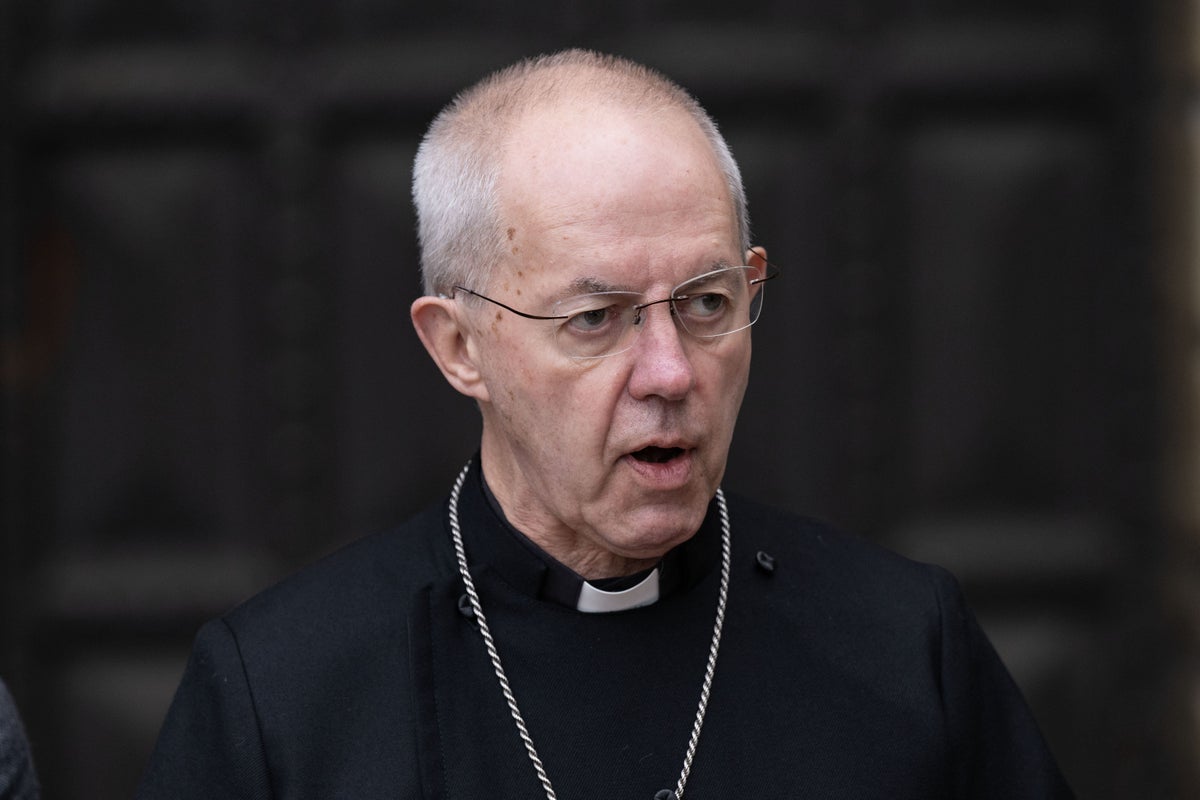

Indian Hindu Kanwarias, worshippers of Hindu god Shiva, offer prayers after taking holy dips in the Ganges River, in Prayagraj, in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, July 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Rajesh Kumar Singh)

The controversy triggered widespread outrage on July 17 when the Uttar Pradesh police issued the directive in Hindi, saying that in the past, confusion over eateries had led to lawlessness and communal violence. In recent years, India has seen a spike in “cow vigilante” violence, in which Hindu mobs attack people, usually Muslims, alleged to have consumed or sold beef that some Hindus consider sacred.

“To prevent such recurrences and given the faith of the devotees … hotels and shopkeepers selling food items on Kanwar [Route] have been requested to display the names of their owners and employees voluntarily,” the police order said.

This did not sit right with Khan. The rights advocacy group filed a petition in India’s top court, a common tactic in India to request judges to block an order deemed unconstitutional.

“Once they start this segregation in the name of this religion, it will snowball far ahead of this pilgrimage’s route and seep into the other states,” Khan said. “Before we know it, it will be the new status quo.”

When he reached out to the impacted shopkeepers in Muzzafarnagar, Uttar Pradesh, Khan said, the owners were afraid to come on board with the petition. “They told us that it is just a matter of 15 days,” Khan recalled. “They said closing the shop for 15 days is better than having your home bulldozed.”

BJP-ruled states have increasingly targeted Muslim families by bulldozing their homes, which Amnesty International has described as deliberate “punishment to the Muslim community.”

The fear of repercussions travels far beyond this town, Khan noted, with thousands of families losing their livelihood due to both official and unofficial bans on beef sales.

An increasing number of Hindu pilgrims in particular are committing violent crimes against Muslims. In Muzaffarnagar, two rickshaw drivers were recently beaten and their vehicles attacked, while in a separate incident a Muslim driver was thrashed and his car vandalized. In other attacks, a security guard was beaten and a petrol pump vandalized. In videos of the attacks shared on social media, police were present but did not intervene.

“There is complete free hand given to Kanwardiyas (pilgrims),” Khan said. “We are falling short on institutions that have a responsibility to implement (the Supreme Court’s orders) while the police are acting one-sided.”

Earlier, the Uttar Pradesh police have also faced criticism for showering rose petals on the Kanwar Yatra and massaging the feet of pilgrims.

“Muslims have lost faith in the police, and therefore, they are shutting down businesses,” Khan said. “This symbolizes the collapse of the state authority in India.”

Apoorvanand Jha, a professor at the University of Delhi and a columnist who goes by his first name, remembers joyous pilgrims from his childhood in Bihar and Jharkhand, two states in eastern India, journeying on the long walks to the Ganges.

Hindu pilgrims, known as Kanwarias, gather on the banks of the Ganges in Prayagraj, India, July 16, 2023. (AP Photo/Rajesh Kumar Singh)

“Now, the BJP government has given a very exalted status to the Kanwar Yatra and turned them into a group that is supreme and cannot be touched,” Apoorvanand said. “The police is compliant and some of the pilgrims behave as if they were placed on a pedestal and turned into a kind of semi-god.”

To him, the dictate to display names on signboards was “outrageous” — and pushed him to join other petitioners to the top court.

“The state apparatus is indulging in a majoritarian behavior, which makes it even more dangerous, and it should not be given a free pass,” he said.

The millions of pilgrims are seen as “vote-banks” by the lawmakers, Apoorvanand and Khan agreed.

In India’s recent national election, the BJP lost the parliamentary majority. It was a major upset for the party that had ruled since Modi’s rise to prominence in 2014. Today, the BJP retains control of the government through allies in the Parliament. A coalition of opposition parties campaigned over issues of social justice and a vision of India as ethnically and religiously diverse, aiming to contrast the BJP’s emphasis on maintaining a Hindu nation.

However, since the new session of the Parliament, human rights groups have questioned the silence of opposition leaders regarding the persecution of minorities, including Christians and Muslims.

“The opposition leaders believe they cannot afford to alienate Hindus,” Apoorvanand said. “But it is also a sad commentary on India’s Hindu society … that political parties think that a majority of Hindus endorse this violence — and you cannot criticize them.”