As President Donald Trump’s rhetoric against Iran heats up again, it is worth recalling a time when the two countries had a distinctly different relationship.

That time began in the 1800s, as American missionaries journeyed to what was then called Persia.

The missionaries helped build important institutions – schools, colleges, hospitals and medical schools – in Persia, many of which still exist.

You may be interested

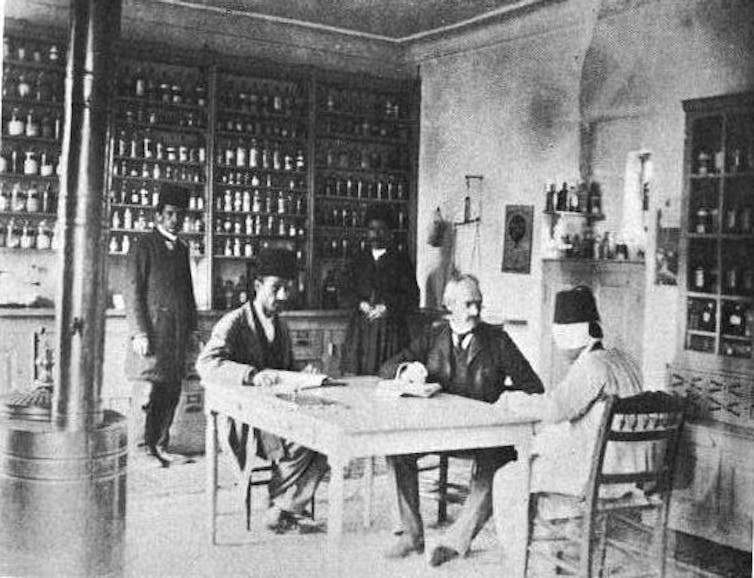

So when Dr. Joseph Plumb Cochran, an American physician fluent in Persian, Turkish, Kurdish and Assyrian, died at Urmia in northwestern Iran in 1905, over 10,000 people attended his funeral.

Cochran founded a hospital in Urmia in 1879, as well as Iran’s first medical school.

This image clashes with most American stereotypes of Iran and its people, and is at odds with decades of anti-Iranian sentiment emanating from Washington.

Iran and the United States, in fact, have a deep history of mutual respect and friendship.

From 1834, when the first Protestant American mission was established in Urmia, until 1953, when the CIA’s involvement in Iran’s internal affairs set the United States on the road to conflict with Tehran, Americans were the good guys.

Imperial bad guys

My interest in the history of Iranian-American relations stems from 45 years as an archaeologist specializing in Iran, and from research on Iranian history in the context of changes undergone by Iran’s nomadic population through time.

For years, Americans have seen images of Iranians shouting “Death to America.” Now it’s the country’s lawmakers doing it. President Trump returns the sentiment, recently threatening Iran with death and destruction.

But before all that happened, when Americans were the good guys, there were other countries who were instead reviled by Iran.

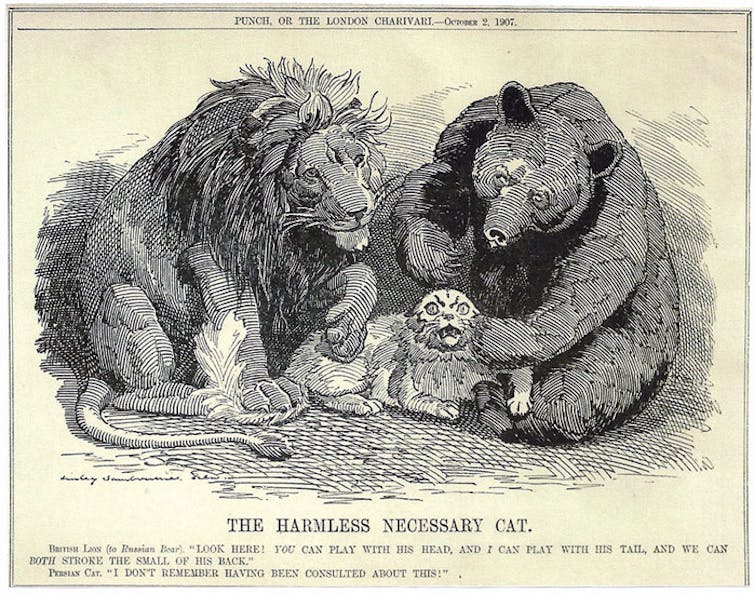

The bad guys, at whose hands Iran suffered most, were Russia and Great Britain. Those two nations – often at the invitation of Iran’s leaders – economically exploited Persia to further their own imperial ambitions, using sustained diplomatic, military and economic pressure.

After two ill-judged wars fought against Russia – the First (1804-1813) and Second Russo-Persian Wars (1826-1828) – Persia (the name Iran was officially adopted in 1935) lost large amounts of territory to the Czar.

Much later, Russia found another means of exerting control over the Persian crown, loaning millions of rubles to its rulers, like Mozaffar ed-Din Shah, who reigned from 1896-1902 and needed capital to fund his lavish lifestyle.

With the exception of the Anglo-Persian War (1856-1857), Persian relations with Great Britain were less openly hostile. But what they lacked in martial vigor was more than compensated for by economic exploitation.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the shah granted exclusive concessions to the British for everything from telegraph lines to tobacco. Rights to Iran’s oil were given to the Anglo-Persian (later Anglo-Iranian) Oil Company.

So assured were Britain and Russia in their control of Persia that, in 1907, they signed the infamous Anglo-Russian Convention. That agreement divided the country – unbeknownst to its Parliament, let alone its inhabitants – into Russian, British and “neutral” spheres of influence. After it became public it provoked the outrage of ordinary Persians and the international community at large.

America the good

Iran’s relations with the United States were completely different.

The 19th- and early 20th-century history of British and Russian imperial ambitions and involvement in Iran put Iran in a dependent, exploited position at the hands of the governments of these two countries.

But the presence in Iran of American missionaries and, later, invited government technocrats was of an entirely different quality. These were Americans offering aid, with no expectation of advantage to be gained officially for the United States government.

American Presbyterian missionary efforts in Iran began in 1834 and focused on education, with 117 schools established around Urmia by 1895. Efforts were also directed at medical and social welfare. These were nongovernmental missions. The U.S. government was conspicuous by its absence in Iran and Iranian affairs.

By the late 19th century, the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions had opened new stations in cities across northern Iran, from Tehran to Mashhad. American diplomatic relations with Persia were established in 1883. A decade later the American Presbyterian Hospital was founded in Tehran by John G. Wishard.

After the First World War, Presbyterian schools for both boys and girls proliferated, the most famous of which were the American College of Tehran for boys, established in 1925, and Iran Bethel School for girls.

In 1910, the Persian Parliament, aware that their country’s finances were in disarray, invited the U.S. to identify a “disinterested American expert as Treasurer-general to reorganise and conduct collection and disbursement of revenue.”

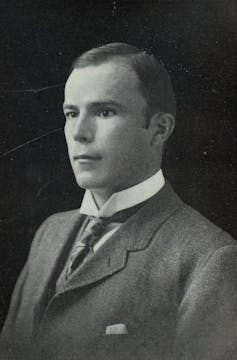

Despite Russian attempts to block the initiative, W. Morgan Shuster, a distinguished career civil servant, was appointed by Persia in February 1911. He arrived in Tehran in May, bringing with him four other Americans. The mission was a failure, lasting only eight months, and, unsurprisingly, was adroitly sabotaged by the combined efforts of British and Russian diplomats in Tehran.

The country’s financial situation after the First World War was still precarious. With none of the colonialist baggage associated with the two European superpowers, America was turned to, almost as a last resort, to fix what ailed Iran. Riza Shah (father of the last shah) appointed an American, Arthur C. Millspaugh, as the administrator-general of the finances of Persia.

When Millspaugh arrived in Tehran in 1922, a newspaper editorial addressed him with these words: “You are the last doctor called to the death-bed of a sick person. If you fail, the patient will die. If you succeed, the patient will live.”

Despite his often testy relations with foreigners, Riza Shah acknowledged Millspaugh’s American Financial Mission was “the last hope of Persia.” The fact that the mission was far from an unqualified success does not detract from its importance. Nor did it diminish America’s image as an honest broker in Iranian eyes, in contrast to that of Russia and Great Britain.

Of course, not every Iranian-American interaction during this period was positive. Robert Imbrie, the American consul in Tehran, was brutally murdered in 1924, allegedly because a fanatical religious leader accused him of being a Baha’i and poisoning a well. Riza Shah used the episode to crack down on dissidents and impose strict controls on public gatherings.

America the bad

America’s benign image in Iran was forever shattered in 1953 when the CIA, working with Great Britain, engineered a coup against the democratically elected prime minister, Mohammad Mossadegh, who had nationalized the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company.

Even though the overthrow of Mossadegh damaged Iranian trust in America, the years just prior to Iranian revolution in 1979 saw the number of Iranian students in the United States steadily rise.

Over one-third of the approximately 100,000 Iranian students pursuing university degrees abroad in 1977 were in the U.S. By the time of the Islamic revolution two years later, that number had climbed to 51,310, making Iran by far the biggest single source of foreign students in America, with 17 percent of the total foreign student population. The next-largest contributor of foreign students, Nigeria, accounted for only 6 percent.

“Iranian students have been here for nearly a century . . . there are deep and abiding connections that reveal themselves when you look at the historical record,” researcher Steven Ditto, who wrote a report on Iranian students in the U.S., told the Washington Post in 2017.

Even today, some Iranians still manage to overcome the hurdles they face in studying in America. Two of my current Ph.D. students in Near Eastern archaeology come from Iran. In 2017, there were 12,643 Iranian students in the U.S.

The legacy of American goodwill, personal friendship and doing the right thing by Iran has not been completely lost, although scenes of anti-American demonstrations against the Great Satan on the streets of Tehran – some organized by the government – may make it seem as though America’s good relationship with Iran has been lost irretrievably.

Deep friendships dating back well over a century can withstand a great deal. A reservoir of goodwill and affection may lie dormant while political storms rage. Iran and America were good friends in the past, and for good reason. I believe that Americans would do well to remember that.