Special Envoy to Combat Antisemitism

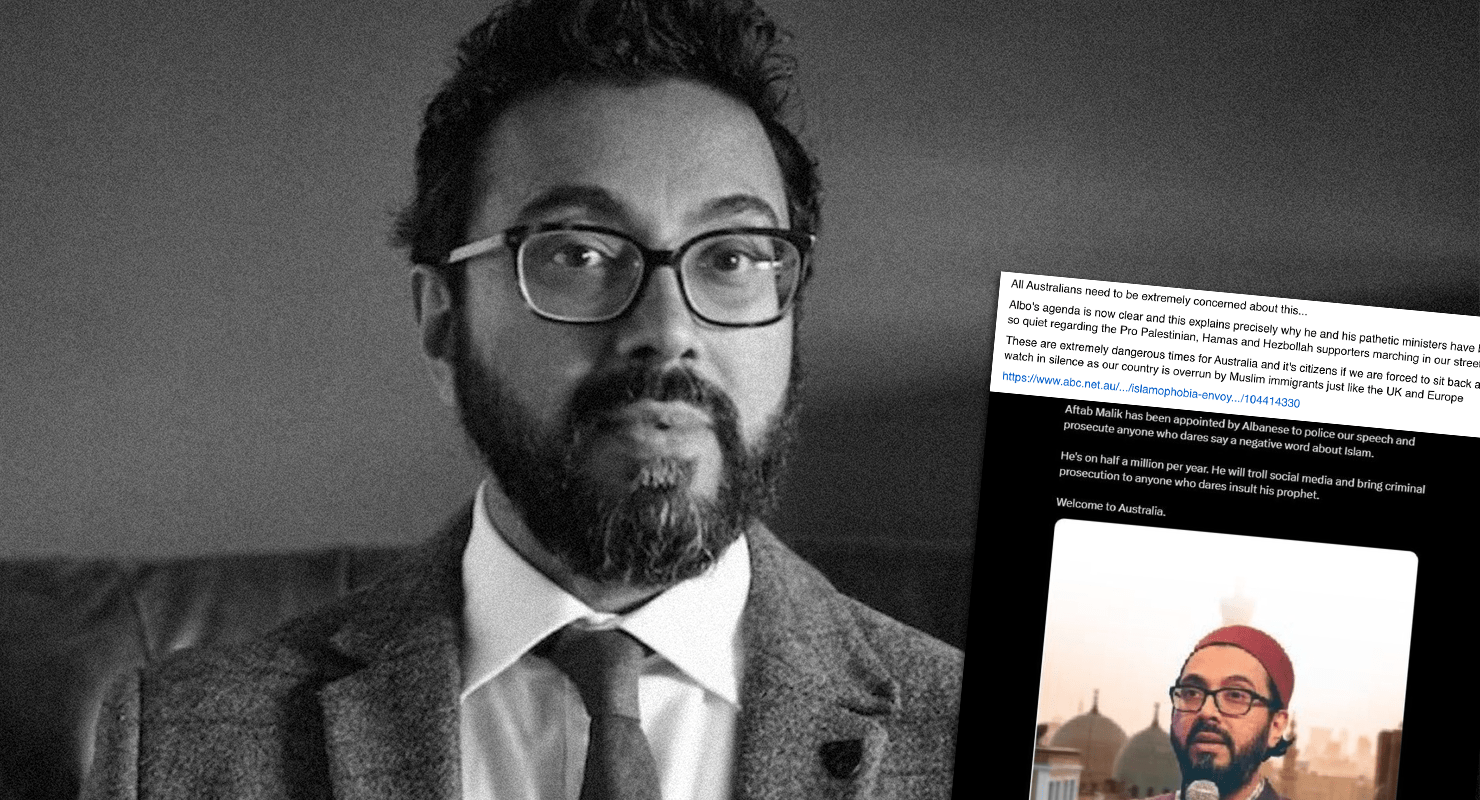

Nearly three months after Jillian Segal’s appointment as the federal government’s “Special Envoy to Combat Antisemitism”, and just hours before it was due to cross the threshold beyond which Bilal Rauf from the Australian National Imams Council had said that the process would become “almost farcical”, the government has finally announced the appointment of Aftab Malik as the “Special Envoy to Combat Islamophobia”.

It is more than appropriate for the government to take action against the surge in both antisemitism and Islamophobia in the wake of the October 7 Hamas attack against Israel. However, the use of envoys to undertake this was a farce from the outset.

Antisemitism Envoy Created Following Lobbying Efforts

As academic Jordana Silverstein has noted, the role of the antisemitism envoy was created in response to lobbying by local Zionist organisations for an Australian envoy to attend the World Jewish Congress in Argentina in July, alongside similar envoys from around the world. It was not an organic response to local circumstances, and the appointment of an Islamophobia envoy for “balance” is even less so.

You may be interested

The fact that Aftab Malik has until now been relatively unknown in Muslim community politics is not in itself a bad thing, given the very fine line between “well-known” and “notorious”. His British-Pakistani background is not a typical Muslim identity in Australia, where despite the recent rapid growth in migration from Pakisitan, Pakistani community organisations remain overshadowed by their much-larger and long-established Lebanese and Turkish counterparts. This is offset by the fact that Malik migrated to Australia in 2012 to take up the role of scholar in residence at the Lebanese Muslim Association.

projects on countering violent extremism

However, his subsequent position with the New South Wales state government and his record of running government-funding projects on countering violent extremism will reinforce suspicions among many Muslims that he is simply yet another government flunky, rather than a bridge for communication. The appointment of a male envoy has also drawn criticism in some Muslim social media spaces, given that women are the primary targets of Islamophobia, as well as its most articulate opponents. (Of course, such criticism rests on the dubious assumption that there are any women who actually wanted the job).

The identity of the envoy is less important than the fact that this position simply should not exist in the first place. The delay in announcing the appointment was partially due to the need to consult with the relevant communities, but mostly because nearly all of those approached could detect a poisoned chalice when it was shoved under their noses, reeking of arsenic. Why should Muslims believe that the envoy will be a more effective vehicle for addressing Islamophobia than established institutions such as the Australian Human Rights Commission? And why should we believe that the envoy will be taken any more seriously than Senator Fatima Payman, whose reasons for crossing the floor (and eventually leaving the ALP) reflect the concerns of the vast majority of Muslims living in Australia?

Envoys Tasked with Managing Regional Fallout

The primary task of the envoys will be to manage the local fallout from the bloodshed in Israel, Palestine, and now Lebanon. But this is not a religious conflict and the Islamophobia envoy will not represent the experience of Palestinian and Lebanese Christians. Nor does the antisemitism envoy represent the concerns of many Australian Jews, as Silverstein and others have articulately stated. John Howard chose to use interfaith dialogue as a way of avoiding the word “racism”. Having just scolded the organisers of The Muslim Vote for (supposedly) attempting to introduce a faith-based political system to Australia, Anthony Albanese is now taking inspiration from confessional states such as Lebanon by deploying religious envoys to “manage” community tensions.

Yesterday’s long-awaited announcement of the Islamophobia envoy has been welcomed even by Muslim community leaders such as Bilal Rauf who had earlier been critical of the process. However, the use of envoys is at the very best a waste of money that could be more usefully deployed in existing, holistic antiracism campaigns and education. At worst, it reinforces the divisions that the envoys are supposed to overcome. And in the meantime, Australia’s foundational racism against First Nations peoples will remain on the sidelines, where it was kicked after the failure of the Voice referendum.

Are special envoys an effective way of addressing antisemitism and Islamophobia? Let us know your thoughts by writing to [email protected]. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.