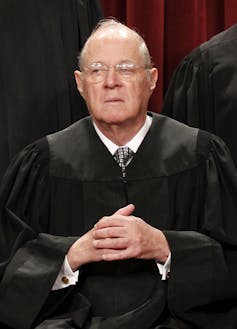

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission is one of retiring U.S. Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy’s most maligned rulings. Many condemn the opinion for treating corporations as people, money as speech, and elections as commodities to be sold to the highest bidder.

President Barack Obama lambasted Citizens United in a State of the Union address. During her 2016 presidential campaign, Hillary Clinton promised to nominate a Supreme Court justice who would overturn it.

Citizens United does not deserve such scorn.

You may be interested

As an election law scholar who has litigated campaign finance cases, including in the U.S. Supreme Court, I believe Citizens United is a straightforward application of free speech principles and, like Kennedy’s jurisprudence as a whole, reflects a balance of conservative and liberal legal conclusions.

The history

Citizens United was a non-profit corporation that received “a small portion of its funds” from for-profit corporations.

In 2008, while Hillary Clinton was seeking the Democratic Party’s nomination for President, it released a documentary called Hillary: The Movie. The film featured numerous interviews with people who, the Supreme Court explained, were “quite critical” of her.

Citizens United wanted to pay a cable company $1.2 million to make the documentary available for free, on demand, to the company’s subscribers. It also wished to air paid advertisements for the movie.

Federal law, however, prohibited corporations from spending money to expressly advocate a federal candidate’s election or defeat. This restriction applied to Hillary: The Movie because Citizens United had accepted some corporate funding and the film amounted to express advocacy.

Citizens United sued, arguing these restrictions violated its First Amendment rights.

The ruling

Kennedy’s opinion in Citizens United blended conservative concern for free speech with a more liberal focus on transparency.

The conservative majority held corporations have the right to create and distribute political advertisements and other election-related communications such as Hillary: The Movie.

All the justices except Clarence Thomas joined in the final part of the opinion, which held that the government may require speakers like Citizens United to publicly report such expenditures and include disclaimers on their election-related communications, revealing who paid for them.

Citizens United ended unnecessary restraints on political expression and gave voters access to a wider range of election-related information. It also afforded corporations a fair chance to present their perspective on elections that could have tremendous consequences for them.

Corporations are taxed and subject to government regulation. They play vital roles in providing the jobs, goods and services that drive our economy. It is only fair to allow corporations to voice their institutional views about candidates for public office — views that voters, of course, are free to completely disregard.

Money, speech and collective political action

Critics claim Citizens United allowed corporate America to buy elections.

The central question in the case, however, was whether corporations could spend money to engage in election-related speech. It remains illegal for corporations to contribute money to candidates, political parties or traditional political action committees (PACs).

Moreover, most of the principles Citizens United relied upon were established in cases decided decades earlier.

The 1976 landmark case Buckley v. Valeo set forth the constitutional principles governing modern campaign finance law. It reaffirmed that election-related speech lies at the heart of the First Amendment. And it recognized that, while money is not literally speech, it is essential to virtually every form of political speech.

Political signs require poster board and markers. Political flyers must be duplicated. Political advertisements cost money to broadcast or publish.

Limiting political spending, the Supreme Court explained, reduces “the number of issues discussed, the depth of their exploration, and the size of the audience reached.” The government may not limit political expression, the court emphasized, just because it costs money. Rather, such “independent expenditures” remain pure political speech entitled to maximum constitutional protection.

In the decades after Buckley, the Supreme Court held that people retain this right to engage in pure election-related expression when they join together to achieve political goals collectively. Groups such as political action committees, political parties and certain non-profit corporations have the First Amendment right to spend money to fund election-related speech without government limits. Several liberal justices joined in many of these rulings.

Citizens United extended to for-profit corporations the same constitutional right to advocate for or against candidates that other types of private associations – as well as the corporations’ stockholders, directors, executives and employees – already possessed.

A trickle, not a flood

Critics proclaimed that Citizens United would open the floodgates to a deluge of corporate political spending.

They were wrong.

University of New Mexico Professor Wendy Hansen and her co-authors discovered that, in the 2012 election, “not a single Fortune 500+ company” made independent expenditures. And only nine Fortune 500 companies made contributions to SuperPACs, totaling less than $5 million.

This trend persisted in ensuing elections. The Conference Board’s Committee for Economic Development reports that only 10 corporations made independent expenditures in 2016, and they totaled less than $700,000.

Such results are unsurprising. Most major corporations do not want to alienate up to half their potential customers by spending millions of dollars publicly aligning themselves with a particular candidate or political party.

What about SuperPACs?

A more substantial objection is that Citizens United paved the way for “SuperPACs.”

SuperPACs are political committees that only fund election-related speech and activities without input from candidates. Because SuperPACs cannot contribute to candidates or political parties, people may give unlimited amounts of money to them.

Citizens United didn’t create the principles that led to SuperPACs; Buckley did. SuperPACs simply let people join together to engage in the same political speech and spending they were already free, under Buckley, to perform on their own.

Kennedy’s opinion in Citizens United did not cause a corporate Armageddon for our political system. It was a victory for the fundamental First Amendment right of all Americans, individually or collectively through corporations, to engage in pure political speech about federal elections.