An exhibition at the De Young Museum offers a snapshot of the how women dress in today’s Islamic cultures, from the austere to the brightly colored, the athletic to the couture.

San Francisco

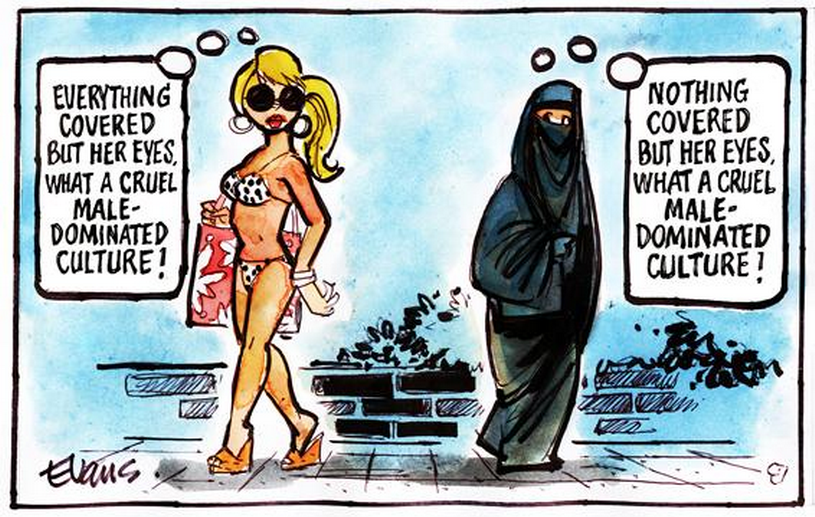

‘She wore the burkha,” Paul Scott writes of a Muslim woman in “The Day of the Scorpion,” the second novel in his masterpiece of 1940s India, “The Raj Quartet.” He describes the garment as a “head-to-toe covering that turns a woman into a walking symbol.” This, perhaps, is how many in the West see the burqa, and also the hijab (a covering for the head and chest) and the niqab (a face veil)—cloth cloisters of Islam, the second-largest religion in the world. Does this woman-as-symbol express strong self-possession or female submission, respect for her religion or an Orientalist echo of the harem? To veil or not to veil? To wrap or not to wrap? These are existential questions—spiritual, political and generational, too—and the answers are often met with prejudice. In the exhibition “Contemporary Muslim Fashions,” the De Young Museum looks at a paradigm of dress that is a daily reality for one billion women world-wide.

You may be interested

For many, it may come as a surprise that there is such a thing as Muslim fashion, style that goes beyond a draped and seemingly shapeless silhouette. But as Igor Stravinsky once wrote, “The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees one’s self.” What are Islam’s constraints for women? Covered head, arms and legs, no décolletage and a waist defined gently if at all.

The exhibition’s organizers—Jill D’Alessandro and Laura L. Camerlengo, respectively curator in charge and associate curator of costume and textile arts at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco—remind us that “Islam is a multicultural faith,” which means that interpretations of these constraints have been variously shaped by local customs, fabrics and indigenous craftsmanship. The curators also point out that theirs is not a definitive survey, the subject is too big. Instead they offer “a current snapshot of Muslim women and fashion by spotlighting key themes, locations, and garments.” This show is a fresh corrective to the narrow perception one may have of Muslim dressing, or as it is now often called, “modest fashion.” After closing at the De Young, the exhibition will travel to Frankfurt’s Museum Angewandte Kunst.

The viewer is greeted by four formal ensembles in black and white, the grouping flanked by an Arabic mashrabiya, the geometrically latticed window that is an architectural form of veiling. An ethereal white coat by Wadha Al Hajri (spring/summer 2017), which repeats the intricate mashrabiya pattern in cut silk organza, is of a beauty that transcends time and place. Even the most traditional of these four pieces, Datin Haslinda Abdul Rahim’s hooded, hip-length white chador over a long white skirt—a praying ensemble embellished with delicate diamanté leaves (spring/summer 2017)—could be taken for an exquisitely abiding Western wedding dress. It should come as no surprise that modest fashion has an increasing following of non-Muslim buyers, women who no longer wish to let it all hang out.

Presenting approximately 80 ensembles by over 45 designers, the exhibition resides in a large gallery fitted with wall panels curved arch-like at the top and positioned to create three long corridors. The sacred space of a mosque is evoked, as well as the space-module curves of futuristic ’60s mod. Fealty and the future; the mosque, modernity and the millennium—this is the nexus of “Contemporary Muslim Fashions.” That welcome in black and white is a tease, because the ensembles on display boast the vivid, saturated, gilded, even neon color, and the decorative dynamics, of Islamic art. There is nothing abstemious or old hat here.

The exhibition’s themes begin with “Covering,” which is addressed through provocative contemporary photographs, all of them alive to the ways modesty connects with multi-leveled statements of identity. Two vintage photographs from 1979, however, by Iranian artist Hengameh Golestan, are more political than personal: they record the female demonstrations that protested newly mandated veiling in public spaces. Such photography, joined by art and video, bring lived context to the clothing.

We then move on to themes that include “The Middle East,” “Social Media” (a platform that has allowed young Muslim women to air their sartorial philosophies), “Sportswear” (Nike jumped on the “modest” bandwagon in 2017), “Southeast Asia” and “Global Fashion.” There is overlap between these themes, so it’s best to just go with the flow. And what flow! Playful street style, avant-garde experimentation, and high-end luxe with a vengeance—these creations open a door on modest sensibilities that are as up-to-the-minute as mainstream fashion. Just not as hourglass. Or as bare.

The exhibition’s grand finale is a gathering of couture creations—Karl Lagerfeld, John Galliano, Oscar de la Renta and more. The hundred-year history of wealthy Muslim women buying Paris couture, which they could customize to meet religious requirements, coupled with the unsung fact that oil-rich Muslims have helped keep the couture alive for decades—this subject alone could make for an exhibition. And yet it’s the third corridor that holds the knockouts. Malaysian design team Fiziwoo’s extravagantly enfolding “Red Rose” ruffle gown of 2015. Itang Yunasz’s jazzy caftan and folkloric embroidered jacket, both from 2018. And Bernard Chandran’s 2008 asymmetrical jumper over a top and pants, all silver silk and Swarovski crystals, celestial discipline and the Vulcan wisdom of Spock. Make way for modesty.

—Ms. Jacobs writes about culture and fashion for the Journal.

This article originally appeared on wsj.com